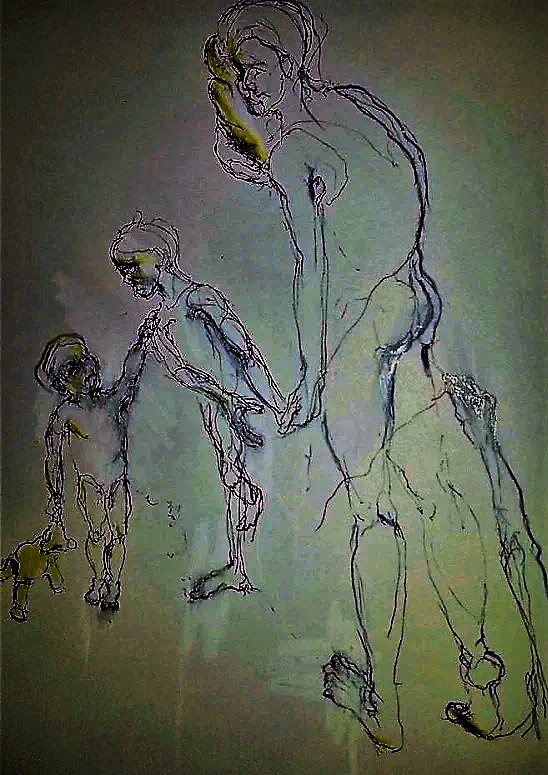

Front picture by Vanessa Haines Matos. www.climatenatureemergency.org

***

Art enables us to connect different realities together. This capacity of art is what makes it also spiritual, transcending into other levels of experience, thereby enabling a transformation.

A performance dancer mediates between worlds. The work of connecting different realities is similar to that of a healer. These were among the many things taught to me by the performance dancer Ana Kavalis.

In her practice and approach to art, Ana builds on different meditative and bodily practices ranging from the Sufi whirling dance to the Japanese Butoh performance dance. Elements of these were present in the hour-long warm-up exercise of her workshop “Corpo Migrante” held in São Paulo. The warm-up included activating senses and voice to connect to our core and getting released from the ordinary ways of perceiving and sensing.

The exercises were physically demanding and included opening up vocal canals. The purpose was to enable connecting with one’s senses. For Ana, when the body is tired, the ego decreases. One is not creating anymore from a manipulative standpoint. The warming-up exercise functioned as a way of “cleaning” oneself and decreasing anxiety inherent in social interactions.

The music had a repetitive quality to enable forgetting all the things that may hinder from focusing on the present moment.

Ana understands the performance artist as a type of healer of society, who deals with themes that are pressing in the world and puts them in her body. The performance artist tells stories, and to be able to do so, they listen to their world. Like healers, they access intuition. She uses her body to open things, to let them loose, to liberate, as in a cathartic ritual, just like in Greek theatre.

Ana herself entered the spiritual dimension of her work through her experiences with Ayahuasca. She reminds me that the word spirit comes from spiral, which comes from dreaming. It is also related to the word in Latin languages referring to breathing (e.g. Spanish respirar).

The very last exercise in Ana’s workshop was a practice of the “healing touch”, which Ana had learned from a Chilean performance dancer. The practice consisted of one participant lying on the floor, and another one touching her in different spots, and “healing” through touch. It was an indigenous practice.

For Ana, the exercises done in a group, in the manner of a ritual, have the ultimate function of placing humanity at the center. Art brings us closer to nature as it reminds us of our carnality, that we are nature. It takes this essence to another level through the poetic, full of significations and symbols.

The New Age and the Occult are perhaps some forms of experimenting with Nature’s subjectivity. Ana has conducted a performance with “urban witches” in Berlin, who are migrant women in the process of searching for a deeper connection, with self, the other, nature and its energies. The performance surged after interviews with various self-identified witches living in Berlin, who came from South Africa, Spain, Uruguay and Ireland. Many of them had sought refuge in witchcraft to liberate themselves from things like conservative family rules that haunted them from childhood.

Why would urban globetrotters – otherwise also called migrants – find witchcraft appealing?

Ana views that, as religions are perceived increasingly as dogmatic, there are fewer avenues to feed one’s spiritual cravings. In part, art – just like practices of modern witchcraft – can fill the gap. From when she was little in Cuba, Ana learned that we don’t know everything about the world, nor do we understand its energies. In Cuba, everyone had respect for the occult.

The modern witches Ana encountered in Berlin were in some way or another all looking for rootedness in a global society. In today’s fast pace, we need something to grab onto. We are told that our purpose is to consume and produce, to generate growth to achieve well-being. Witchcraft defies that narrative. Many of the witches were re-signifying their intuitive power, and connecting with a magical world that was at the same time simple and uncontrollable. They create their practices by combining rocks, tarot, candles, – a little bit from here and there.

There is politics involved in spirituality, although many would not use the word “politics”.

It is hard to separate modern witchcraft from feminism. Ana has been greatly inspired by Silvia Federici, who has written The Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation. Federici demonstrated the link between land enclosures, the birth of capitalism and witch hunts. She writes how in the new organisation of labour (16th century) women became property: all their labour was usable, like water or air. This occurred when all female activities came to be viewed as non-work.

The cycles of the moon that are often intensily followed by witches and magicians link to women’s reproductive cycles. Menstruating has in pre-industrial and non-Christian-Judeo societies been a powerful, magical, and dangerous attribute of women. Barbara Tedlock writes how in many societies women are closer to the spiritual realm when menstruating, hence their seclusion. A seclusion hut was for a woman a time of freedom: the time she was powerful. The power was so great it caused envy in the opposite sex. In Papua New Guinea men even conduct rituals of symbolic blood-shedding through their noses in an attempt to mimic the power women have in their menstruation.

Anthropologists working with evolutionary theories have also paid attention to the role of menstruation and power in the evolution of culture. Prior to the invention of agriculture, the moon held an important role in governing human cycles, and it was the time women synchronised their menstruation, or at least played they synchronized it. For Chris Knight, it was a strategic practice initiated by women to send men hunting during the full moon.

Indeed, for anthropologists studying rituals, there is a direct link between ritual and the birth of language[1]. The more recent turn into more-than-human worlds however challenges evolutionary biologists’ excessive focus on the birth of human culture. In the “Primacy of Movement” Maxine Sheets-Johnstone argues that the fundamental essence of consciousness is movement. This means that any being that can move – be it an amoeba or bacteria – is also conscious that it is moving. We do not perceive our consciousness but feel it as a different dynamic process [2].

–

To go back to Art as Cultivation, we could argue that the “spirituality” in the practice of Ana, just like in the practice of the urban witches, is also a cultivation of a world that goes beyond the capitalist forces that are driving the Anthropocene, rooted in patriarchy.

Ana and the modern witches are cultivating a larger, feminine transformation that places care for our bodies at the center, creating a sense of rootedness and reclaiming power back from where it was taken. One cannot either avoid considering the practice of the urban witches as a critique towards patriarchal capitalism that often pushes women to migrate more than men [3].

What would a working month look like, where those who identify as women would take time of the month to cultivate their spiritual powers and creative skills, instead of being available for competition in the market, to produce more so we can consume more?

Would we have less production? Perhaps yes, but we would have more creativity, a recipe needed for cultivating transformations away from the Anthropocene.

Text by Jasmin Immonen

Sources & further readings:

Federici, Silvia Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation

Knight, Chris 1991 Blood Relations: Menstruation and the Origins of Culture

Luhrmann, Tanya 1989 Persuasions of the Witch’s Craft, Oxford: Basil Blackwell

Tedlock, Barbara 2005 The Woman in the Shaman’s Body Bantam Books

[1]See for example Knight, C., Studdert-Kennedy, M. & James R. Hurford (eds.) 2000 The Evolutionary Emergence of Language: Social Function and the Origins of Linguistic Form Cambridge University Press

[2]I am referencing the thoughts of Maxine Sheets-Johnstone from the book by Sussu Laaksonen 2023 “Vapaan käsikirjoittajan anatomia”, translated from Finnish as “The Anatomy of the Free Writer”. The possible misunderstandings of the writings of Sheets-Johnstone are mine.

[3]Here I am referring to the context of Abya Yala. See Veronica Gago on Neoliberalism from Below.